CSE 130 - Principles of Computer Systems Design Notes

These are my notes for CSE 130 - Principles of Computer Systems for Spring 2022.

Systems

A system is a set of interconnected components that has an expected behavior observed at the interface with its environment.

Systems can be divided into four categories: emergent properties, propogation of effects, incommensurate scaling, and trade-offs.

-

Emergent properties $\to$ properties that are not evident in the individual components of a system, but show up when combining those components.

-

Propogation of effects $\to$ a small ruption or local change can have effects that reach from one end of the system to another.

-

Incommensurate scaling $\to$ as a system scales in size and speed, not all of its parts will follow the same scaling rules, and things will break as a result.

-

Trade-offs $\to$ trade-offs begin with the observation that there is some limited form of goodness, and the design challenge is to first maximize the goodness, second to avoid wasting it, and third to allocate it to the place that needs it the most.

Large systems are complex, which we can define as:

- Large number of components

- Large number of interconnections between components

- Many irregularities (exceptions complicate understanding)

- A long description formulized as “Kolmogorov complexity”: a computational object as the length of its shortest specification

- A team of designers, implementers, or maintainers

Principles of Complexity

Principle of escalating complexity: adding a requirement increases complexity out of proportion.

Avoid excessive generality: generality increases complexity.

Systems change: as time passes, we may realize that some features aren’t as important as we first thought, or we need new features, or our environment changes (ie faster hardware).

Law of diminishing returns: the more one improves some measure of goodness, the more effort the next improvement will require.

Dealing with Complexity

Modularity: we can analyze and design systems as a collection of interacting subsystems. This allows us to consider interactions between components within a module without having to worry about components from other modules.

- The unyielding foundations rule: It is easier to change a module than to change the modularity.

Abstraction: There must be little or no propogation of effects from one module to another. We should treat other modules as black-boxes, and assume that other modules are working as intended.

- In order for this to work we employ the robustness principle: Be tolerant of inputs and strict on outputs. NOTE: It may be better to just kill a program if the input isn’t what we expected, to avoid propagating effects of bad or faulty inputs that leak to other modules.

- The safety margin principle: Keep track of the distance to the cliff, or you may fall over the edge. We need to track and report all out-of-tolerance inputs.

Layering: One builds on a set of mechanisms that is already complete (a lower layer) and uses them to create a different complete set of mechanisms (an upper layer).

- A layer may be made up of multiple modules, but a module from a given layer may only interact with other modules in the same layer or modules of next higher or next lower layer.

Hierarchy: Start with a small group of modules, and assemble them into a stable, self-contained subsystem that has a well-defined interface. Next, assemble a small group of subsystems to produce a larger subsystem. This process continues until the final system has been constructed from a small number of relatively large subsystems.

We can use binding, which is the process of combining modules to implement a desired feature.

- decouple modules with indirection: Indirection supports replaceability. We can use a name to delay or allow changing of a bind.

Computer Systems have no nearby Bounds on Composition

1) The complexity of a computer system is not limited by physical laws. Computer systems are complex because not only do we have to worry about how computers work at the hardware level (chip design, logic gates, etc), which are bounded by physical laws, but we also need to worry about software limits (which are only really hard-bound by hardware requirements), which are generally bound by how fast people can create it.

- As software grows, we deal with leaky abstractions, where modules don’t completely conceal the underlying implementation details.

2)$\frac{d(technology)}{dt}$ is unprecedented.

- We run into the the incommensurate scaling rule: Changing any system parameter by a factor of 10 usually requires a new design.

Iteration is a key concept, for building complex systems. Let’s start with a simple, working system that meets some requirements, and iteratively improve from there.

-

Design for iteration: You won’t get it right the first time, so make it easy to change.

- Take small steps. Allow for the discovery of bad ideas and design mistakes quickly.

- Don’t rush. Make sure each step is well planned.

- Plan for feedback. Include feedback paths in the designs as well as incentives to provide feedback.

- Study failures. Complex systems fail for complex reasons.

Memory

Memory is a system component that remembers data values for use in computation. Memory can be abstracted into models that have two operations: write(name,value) and value = read(name).

- volatile memory is memory that requires power to retain information. Ex: ram, cache, registers, etc

- non-volatile memory is durable, and doesn’t require power to maintain its contents.

Read/write coherence: result of the READ of a named cell is always the same as the most recent WRITE to that cell.

Before-or-after atomicity: result of every READ or WRITE occured either completely before or completely after any other READ or WRITE.

Threats to read/write coherence and before-or-after atomicity include:

-

Concurrency: systems where different actors can perform

READandWRITEoperation concurrently on the same named cell. -

Remote storage: when memory device is physically distant, we ask the question of which

WRITEoperation was the most recent. - Performance enhancements: optimized compilers and high-performance processors do alot of complex operations at the software and hardware level that can add levels of complexity.

- Cell size incommensurate with value size: large values may occupy multiple memory cells, which require special handling for this case.

- Replicated storage: reliability of storage can be icnreased by making multiple copies of values and placing them in distinct storage cells.

Memory latency is the time it takes for a READ or WRITE operation to complete (also called access time).

Interpreters

Interpreters are active elements of a computer system: they perform the actions that constitute computations.

- instruction reference: tells interpreter where to find the next instruction

- repertoire: set of actions the interpreter will perform when it retrieves an instruction from the instruction reference

- environment reference: tells the interpreter where to find its environment, the current state of which the interpreter should perform the action of the current instruction.

When building systems out of subsystems, it is essential to be able to use a subsystem without having to know details of how that subsystem refers to its components. Names are thus used to achieve modularity, and at the same time, modularity must sometimes hide names.

Indirection: decoupling one object from another by using a name as an intermediary.

A system designer creates a naming scheme, which consists of three elements:

- A name space, which comprises an alphabet of symbols together with syntax rules that specifry which names are acceptable.

- A name-mapping algorithm, which associates some names of the name space with some values in a universe of values.

Communication Links

A communication link provides a way for information to move between physically separated components. It has two abstracted operations:

send(link_name, outgoing_message_buffer)receive(link_name, incoming_message_buffer)

SEND and RECEIVE are much more complicated than just READ or WRITE operations, you need to account for things like hostile environments that threaten integrity of data transfer, asynchronous operations that leads to arrival of messages whose size and time of delivery can not be known in advance, and most signficantly, the message not being delivered.

Naming

When we build systems out of subsytems, we need a way to use a subsystem without knowing its insides. We use names in order to achieve modularity, and at the same time, modularity must sometimes hide names. We approach naming from an object POV, the computer manipulates objects.

Use by value $\to$ create a copy of the component object and include the copy in the using object.

Use by reference $\to$ choose a name for the component object and include just that name in the using object. The component object is said to export the name.

Naming serves two purposes:

- Sharing: We can pass by reference so that two uses of the same name can refer to the same object, which allows different users or the same user at different times to refer to the same object.

- Defering: We can defer an object naming to a later time until we need to decide which object should this name refer to.

A naming scheme is comprised of three elements:

- The name space: which comprises an alphabet of symbols together with syntax rules that specify which names are acceptable.

- The name-mapping algorithm: which associates some names of the name space with some values in a universe of values.

- The value: which may be an object or it may be another name from either the original name space or from a different name space.

We call a name-to-value mapping a binding.

A name-mapping algorithm resolves the name, and returns the associated value, which is usually controlled by an additional parameter, known as the context. There can be naming schemes that have only one context (universal name spaces), or more than one context.

value = RESOLVE(name,context): When an interpreter encounters a name in an object, it first figures out what naming scheme is involved and which version of RESOLVE it should invoke. It then identifies an appropriate context, resolves the name in that context, and replaces the name with the resolved value.

There are three frequently used name-mapping algorithms:

- Table lookup: We treat context as a table of {name, value} pairs.

-

Recursive lookup: A path name can be thought of as a name that explicity includes a reference to the context in which it should be resolved. ex:

/usr/bin/emacs - Multiple lookup: Abandon the notion of a single, default context and instead resolve the name by systematically trying several different contexts.

Table Lookup

Two ways to come up with a context with which to resolve the names found in an object. A default context reference is one that the resolver supplies, wheras an explicit context reference is one that comes packaged with the name-using object. A context reference can be dynamic: if you click HELP, it might send you to a different URL based on the error message.

Recursive Lookup

We have an absolute path name that indicates when we’ve hit the root. We recursively perform this lookup until the most significant component of the path (the rightmost element in file paths), is the least significant component of the path name, at which point the resolver can do an ordinary table lookup using some context.

File systems require that contexts be organized in a naming hierarchy, with the root as the base of the tree. We use cross-hierarchy links, the simplest kind of link is just a synonym: a single object may be bound in more than one context. An indirect name is a more sophisticated kind of link, which allows a context binds to another name in the same name space rather to an object.

Multiple Lookup

Since names may be bound in more than one context, multiple lookups can produce multiple resolutions. We use a search path, which is a specific list of contexts to be tried, in order. The name resolver goes through the names in each context, and the first name found in the list wins, and the resolver returns the value associated with that binding.

- Ex: We use search paths for libraries. If we import a math library, and write our own

sqrt()function, we may run into user-depending bindings, where we have conflicting function names.

When we compare names result = compare(name1, name2) we care about three things:

- Are the two names the same? (“Is Jim Smith the same as Jim Smith”)

- Are the two names bound to the same variable? (“Is Lebron James in the NBA the same Lebron James from high school?)

- Even if both names have the same values, is there one copy of value or two copies of values? (i.e if I change one value, will both change, or just the one I changed)?

Modular Sharing

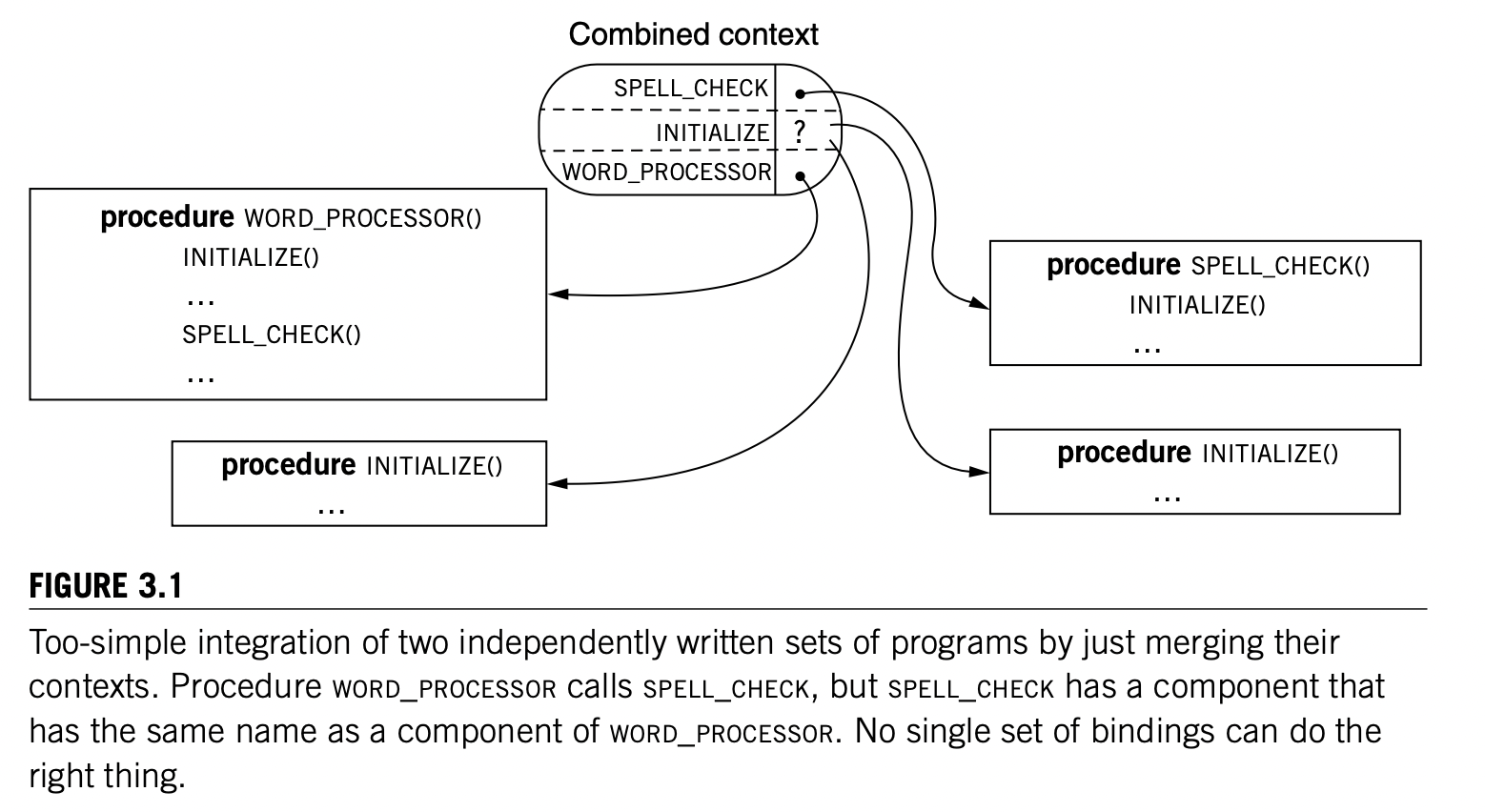

Modular sharing is the idea that we can use a shared module by name without knowing the names of the modules it uses. Name conflict occurs when two or more different values compete for the binding of the same name in the same context.

We can attach a context reference to an object without modifying its representation to associate the name of an object not directly with the object itself but instead with a structure that consists of the original object plus its context reference.

Metadata and Name Overloading

Metadata is information that is useful to know about an object but cannot be found inside the object itself. ex: the name of an object and its context reference.

File names are overloaded with metadata that has little or nothing to do with the use of the name as a reference.

A fragile name is when we overload a name. For example if we store a program in disk05/library/sqrt, and disk05 later becomes full and we move sqrt to disk06, we now need to change all the old file paths to disk06/library/sqrt.

Relative Lifetimes of Names, Values, and Bindings

Names chosen from a name space of short, fixed-length strings of bits or characters are considered limited. If the name space is unlimited, there is no significant constrain name lengths. An object is considered an orphan or a lost object when no one can ever refer to it by name again.

Client/Service Organization

Soft modularity limits interactions of correctly implemented modules to their specified interfaces, but implementation errors can cause interactions that go outside the specified interfaces.

The client/service organization is an approach to structuring systems that limit the interfaces through which errors can propagate to the specified messages and provide a sweeping simplification in terms of reasoning about the interactions between modules.

- Errors can only propagate through specified messages.

- Clients can check for certain errors by just considering the messages.

Enforced modularity is modularity that is enforced by some external mechanism.

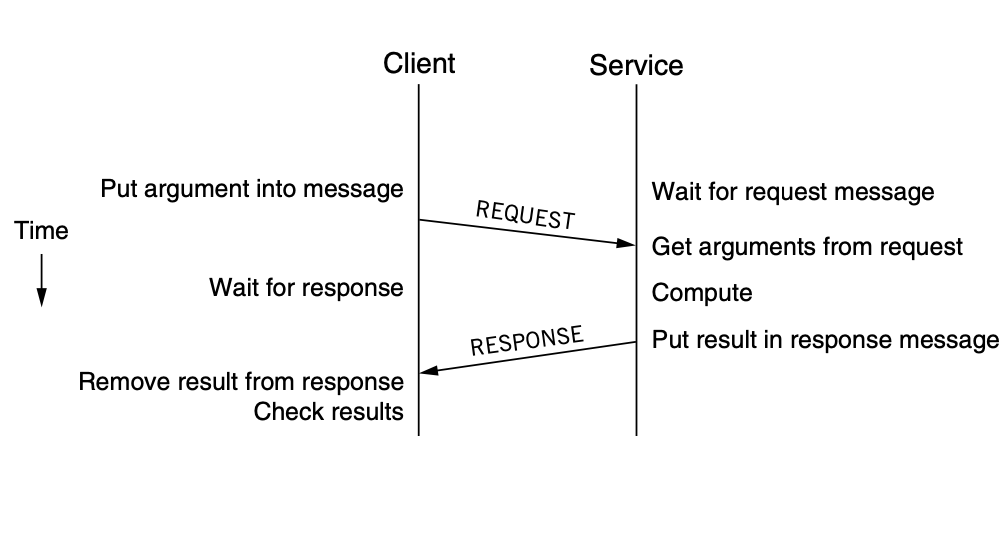

The client is the module that initiates a request: it builds a message containing all the data necessary for the service to carry out its job and sends it to a service. The service is the module that responds: it extracts the arguments from the request message, executes the requested operations, builds a response message, sends the response message back to the client, and waits for the next request.

The above is a message timing diagram of a client/server model, where the client and servers run on separate computers, connected by a wire. We use marshalling, which is a canonical representation so that services can interpret arguments, for example, when the service computer is little-endian and the client computer is big-endian.

Client/service organization not only separates functions (abstractions). it also enforces that separation (enforced modularity).

- Client and services don’t rely on shared state other than the messages, which means errors can propagate form client to service and vice versa, in only one way. (control ways in which errors propagate)

- The transaction between a client and a services is an arm’s-length transaction. (Many errors cannot propagate from one to the other)

- Client can put an upper limit on the time it waits for a response. (avoid infinite loops, failed or forgotten requests, etc)

- Encourages explicit, well-defined interfaces since the client and service can only interact through messages.

The WWW is an example of enforced modularity. The Web browser is a client, and a website is a service; both the browser and the website communicate through well-defined messages and as long as the client and service check for the validity of messages, a failure of a service results in a controlled problem for the browser or the service.

The trusted intermediary is a service that functions as the trusted third party among multiple, perhaps mutually suspicious, clients. Ex: instant message services provide private buddy lists.

Communication Between Client and Service

Remote procedure call (RPC) is a stylized form of client/service interaction in which each request is followed by a response. i.e. a client sends a request, and the service replies with a response after processing the client’s request.

Stubs are a procedure that hides the marshaling and communication details from the caller and the callee.

RPCs differ from ordinary procedure calls in three ways:

- RPCs reduce fate sharing between caller and callee by exposing the failures of the callee to the caller so that the caller can recover.

- RPCs introduce new failures that don’t appear in procedure calls.

- RPCs take more time than procedure calls.

RPCs have a “no response” failure. When there is no response from a service, the client cannot tell which of two things went wrong: 1) some failure occurred before the service had a chance to perform the request action or 2) the action was performed, and then a failure occurred, with only the response being lost. This is solved by 1 of:

-

At-least-once RPC: If a client stub doesn’t receive a stub with a specific time, the stub keeps being resent until it receives a response from the service.

- idempotent: repeating the same request or sequence of requests several times has the same effect as doing it just once.

- At-most-once RPC: If the client stub doesn’t receive a response within some specific time, then the client stub returns an error to the caller.

- Exactly-once RPC: Ideal semantics, but because the client and service are independent, it is in principle impossible to guarantee. If A to B produces a “no response” failure, the client stub can issue a separate RPC request to the service to ask about the status of the request that got no response.

The overhead of an RPC is much higher than that of a local procedure call, resulting in higher latency. We can use caching and pipelining requests in order to hide the cost of an RPC.

Virtualization

Virtualization allows us to virtualize a physical object to simulate the interface of the physical object, by creating many virtual objects by multiplexing one physical instance. It’s virtual because for the user of the simulated object, it provides the same behavior as the physical instance, but isn’t the physical instance.

Threads

We create a thread of execution in order to provide the editor module with a virtual processor. A thread is an abstraction that encapsulates the execution state of an active computation. The state of a thread consists of the variables internal to the interpreter which include

- a reference to the next program step (e.g. a program counter)

- references to the environment (e.g, a stack, heap, etc)

A module with only one thread allows programmers to think of it as executing a program serially: it starts at the beginning, computes, and then terminates. It follows the principle of least astonishment. Modules may have more than one thread by creating several threads wich allows the module to operate the device concurrently.

The thread abstraction is implemented by a thread manager. The thread manager multiplexes the possibly many threads on the limited number of physical processors of the computer so that one error in a thread doesn’t propagate to to other threads.

Bounded Buffer

We use SEND and RECEIVE with a bounded buffer of messages to allow client and service modules on virtual computers to communicate. If the bounded buffer is full when it receives a SEND request, the sending thread will wait until there is space in the bounded buffer.

Emulation and virtual machines provide an interface that is identical to some physical hardware in order to enforce modularity. Virtual machines emulate many instances of a machine.

Virtual Links SEND, RECEIVE, and a Bounded Buffer

The main issue with a bounded buffer is when several threads running in parallel may add or remove messages from the same bounded buffer concurrently. The problem of sharing a bounded buffer between two threads is an instance of the producer and consumer problem. We require sequence coordination: the producer must first add a message to the shared buffer before the consumer can remove it and the producer must wait for the consumer to catch up when the buffer fills up.

One-Writer principle: If each variable has only one writer, coordination becomes easier.

Race Conditions and Locks

Race Conditions are errors that depend on the exact time of two threads. If we rerun the program again, the relative timing of the instructions might have slightly changed, resulting in different behavior.

A lock is a shared variable that acts as a flag to coordinate usage of other shared variables.

- A thread may

ACQUIREa lock, which means other threads that attempt to acquire that same lock will wait until the first thread releases the lock. - A lock is

RELEASEDwhen the thread that acquired it is done using it, and releases it to other threads.

We only want to lock the shared variables which are race conditions. We often use a single acquire protocol which guarantees that only a single thread can acquire a given lock at any one time.

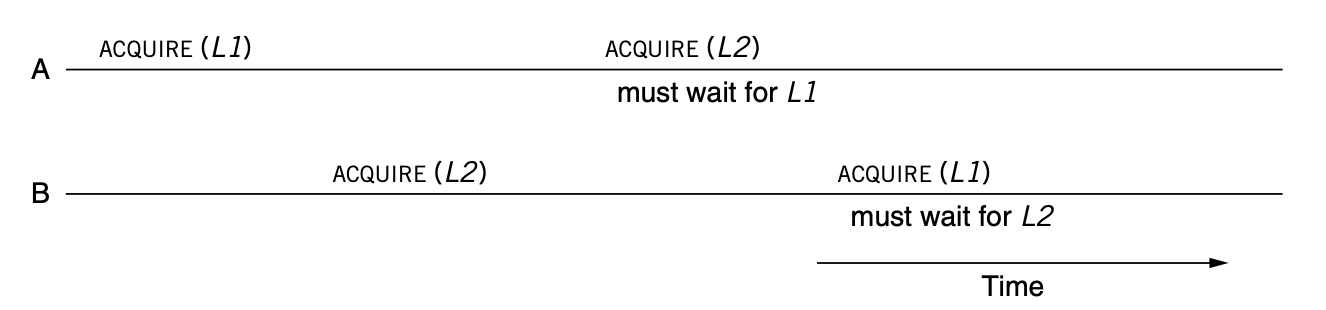

A deadlock occurs when each thread is waiting for some other thread in the group to make progress.

When we deal with multiple locks, we should enumerate all lock usages and ensure that all threads of the program acquire the locks in the same order.

We must ensure that ACQUIRE is a before-or-after action to avoid race conditions.

Virtualizing Processors Using Threads

ALLOCATE_THREAD(starting_procedure, address_space_id) $\to$ thread_id: The thread manager allocates a range of memory in address_space_id to be used as the stack for procedure calls, selcts a processsor, and sets the processor’s PC to the address starting_procedure in address_space_id and the processor’s SP to the bottom of the allocated stack.

An application can have more threads than there are processors, so the problem is to share a limited number of processors among potentially many threads. We first observe that the most threads spend mouch of their time waiting for events to happen. When a thread is waiting for an event, its processor can switch from that thread to another one by saving the state of the waiting thread and loading the state of a different thread (the basic idea of virtualizing the processor).

The job of the YIELD operation is to switch a processor from one thread to another.

- Save this thread’s state so that it can resume later

- Schedule another thread to run on this processor

- Dispatch this processor to that thread

Mutual Exclusion

- No two threads should be in the critical region (CR) at the same time.

- Any number of threads should be supported

- A thread outside the CR cannot block a thread inside the CR

- No thread should starve/wait forever

Performance

We use caching to improve performance:

- Hardware - CPU uses cache to access memory faster

- Operating system - File system caches to avoid disk reads

- Application - Web client uses cache to avoid fetching web pages

- Who systems - modern systems nearly always cache database

Our working set is the set of items used by the k most recent actions. We can usually only cache a subset of our working set, so the question becomes how do we determine what is worth caching?

- temporal locality: recent items are likely to be referenced again soon

- spatial locality: items “near” recently used items are likely to be referenced

Caching consists of keeping recently used items in a way that’s faster to retrieve them and fetching other items that might be referenced soon.

Measuring Performance

Capacity: Amount of a resource that’s available

- Utilization: % of capacity being used

- Overhead: resource “wasted”

- Useful work: resource spent on actual work

We can use time-based metrics such as latency and throughput.