Math for Machine Learning

Some basic math required for machine learning.

Linear Algebra

Mathematically we can think of vectors as special objects that can be added together and scaled.

- $\overrightarrow{x} + \overrightarrow{y} = \overrightarrow{z}$

- $\lambda \overrightarrow{x}, \lambda \in \mathbb{R}$

Systems of Linear Equations

We can formulate many problems as systems of linear equations, and linear algebra gives us the tools for solving them. There are three outcomes for systems of linear equations:

-

No solution: Intuitively, we can think of two vectors that never intersect and run parallel to each other.

\[x_1 + x_2 + \:x_3 = 3 \;(1)\\ x_1 - x_2 + 2x_3 = 2 (2)\\ 2x_1 \hspace{15pt} + 3x_3 = 1 (3)\]

The follow systems of equationssimplifies to this when we add equations 1 and 2

\[2x_1 + 3x_3 = 5 \\ 2x_1 + 3x_3 = 1\] -

1 (unique) solution: Intuitively we can think of two vectors that intersect at one and only one point.

adding (1) + (2) and simplifing gives us $2x_1 + 3x_3 = 5$ which tells us that $x_3 = 1$. From (3), we get that $x_2 = 1$ and therefore are only solution is $(1,1,1)$.

- Infinitely many solutions: Intuitively we can think of two vectors that sit on top of each other on the same line. ie $\lambda\overrightarrow{x} = \overrightarrow{y}$ and $\lambda\overrightarrow{y} = \overrightarrow{x}$

Matrices

Given two matrices $A \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}, B \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times k}$, the elements $c_{ij}$ of the product $C = AB \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times k}$ are computed as

\[\sum_{l = 1}^n a_{il}b_{lj} \hspace{15pt} i = 1,...,m, \hspace{5pt} j = 1,...,k.\]The identity matrix $I_n$ = \(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & \dots & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & \dots & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dots & 1 & \dots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dots & 0 & \dots & 1 \end{bmatrix}\)

tells us that for $\forall A \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n} : I_mA = AI_n = A$

For a square matrix $A \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$, there exists an inverse matrix $B \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$ if the property $AB = I_n = BA$ holds true. Not every matrix $A$ possesses an inverse $A^{-1}$. If $A^{-1}$ exists, than we call $A$ regular/invertible/nonsingular, otherwise singular/noninvertible. If the inverse does exist, it’s always unique.

For $A \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ the matrix $B \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times m}$ where $b_{ij} = a_{ji}$ is called the transpose of A. $B = A^T$. A matrix $A \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$ is symmetric if $A = A^T$.

Given a matrix $A \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ and a scalar $\lambda \in \mathbb{R}$, then $\lambda A = K, K_{ij} = \lambda a_{ij}$. Each element in $A$ is scaled by $\lambda$.

Vector Spaces

Groups: are a set of elements and an operation defined on these elements that keeps some structe of the set intact. Consider a set $\mathcal{G}$ and an operation $\otimes \colon \mathcal{G} \times \mathcal{G} \to \mathcal{G}$ defined on $\mathcal{G}$. Then $\mathcal{G} := (\mathcal{G}, \otimes)$ is called a group if the following conditions hold:

- Closure of $\mathcal{G}$ under $\otimes$: $\forall x , y \in \mathcal{G} : x \otimes y \in \mathcal{G}$

- Associativity: $\forall x, y, z \in \mathcal{G} : (x \otimes y) \otimes z = x \otimes (y \otimes z)$

- Neutral element: $\exists e \in \mathcal{G} \;\forall x \in G : x \otimes e = x$ and $e \otimes x = x$

- Inverse element: $\forall x \in \mathcal{G} \; \exists y \in \mathcal{G} : x \otimes y = e$ and $y \otimes x = e$, where $e$ is the neutral element. We write $x^{-1}$ to denote the inverse element of $x$.

If additionally $\forall x, y \in \mathcal{G} : x \otimes y = y \otimes x$, then $\mathcal{G} = (\mathcal{G}, \otimes)$ is an Abelian group (commutative).

Vector space: A real-valued vector space $V = (\mathcal{V}, +, \cdot)$ is a set $\mathcal{V}$ with two operations

\[+: \mathcal{V} \times \mathcal{V} \to \mathcal{V} \\ \cdot : \mathbb{R} \times \mathcal{V} \to \mathcal{V}\]where

- $(\mathcal{V}, +)$ is an Abelian group

- Distributivity:

- $\forall \lambda \in \mathbb{R}, x, y \in \mathcal{V} : \lambda \cdot (x + y) = \lambda \cdot x + \lambda \cdot y$

- $\forall \lambda , \psi \in \mathbb{R}, x \in \mathcal{V} : (\lambda + \psi) \cdot x = \lambda \cdot x + \psi \cdot x$

- Associativity (outer operation): $\forall \lambda, \psi \in \mathbb{R}, x \in \mathcal{V}: \lambda \cdot (\psi \cdot x) = (\lambda \psi) \cdot x$

- Neutral element with respect to the outer operation: $\forall x \in \mathcal{V} : 1 \cdot x = x$

The elements $x \in V$ are vectors. The netural element of $(\mathcal{V}, +)$ is the zero vector $\pmb{0} = \begin{bmatrix} 0,\dots,0 \end{bmatrix}^T$, and the inner operation $+$ is vector addition. The elements $\lambda \in \mathbb{R}$ are called scalars and the outer operation $\cdot$ is a multiplication by scalars.

Key vector operations are:

- $\mathcal{V} = \mathbb{R}^n, n \in \mathbb{N}$ is a vector space with operations defined as follows:

- Addition: $\pmb{x} + \pmb{y} = {(x_1, \dots, x_n) + (y_1, \dots, y_n) = (x_1 + y_1, \dots, x_n + y_n) } $ for all $\pmb{x, y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$

- Multiplication by scalars: $\lambda \pmb{x} = \lambda (x_1, \dots, x_n) = (\lambda x_1, \dots, \lambda x_n)$ for all $\lambda \in \mathbb{R}, x \in \mathbb{R}^n$

Vector subspaces are sets contained in the original vector space with the property that when we perform vector space operations on elements within this subspace, we will never leave it. Let $V = (\mathcal{V}, +, \cdot)$ be a vector space and $\mathcal{U} \subseteq \mathcal{V}, \mathcal{U} \neq \emptyset$. Then $U = (\mathcal{U}, +, \cdot)$ is called vector subspace of $V$ (or linear subspace) if $U$ is a vector space with the vector space operations $+$ and $\cdot$ restricted to $\mathcal{U} \times \mathcal{U}$ and $\mathbb{R} \times \mathcal{U}$. We write $U \subseteq V$ to denote a subspace $U$ of $V$.

If $V$ is a vector space and $\mathcal{U} \subseteq \mathcal{V}$, than $\forall x \in \mathcal{U} \subseteq \mathcal{V}$ inherit the Abelian group properties, the distributivity, the associativity, and the neutral element. To determine whether $(\mathcal{U}, +, \cdot)$ is a subspace of $\mathcal{V}$ we need to show:

- $\mathcal{U} \neq \emptyset$, in particular $\pmb{0} \in \mathcal{U}$

- Closure of $U$:

- with respect to the outer operation: $\forall \lambda \in \mathbb{R} \; \forall x \in \mathcal{U} : \lambda x \in \mathcal{U}$

- with respect to the inner operation: $\forall x, y \in \mathcal{U} : x + y \in \mathcal{U}$

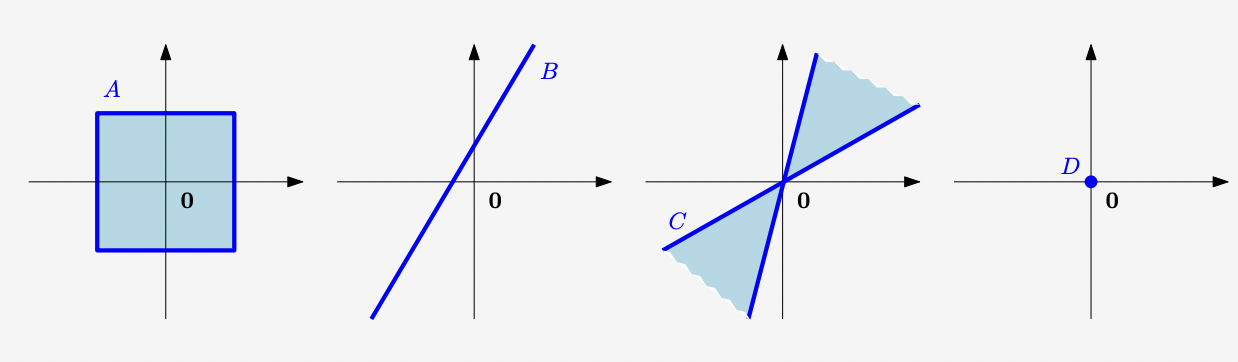

A) Not a subspace $\to$ violates the outer operation principle.

B) Not a subspace $\to$ $0 \not \in V$.

C) Not a subspace $\to$ violates the inner operation principle.

D) subspace!

Linear Independence

Linear Combination: Consider a vector space $V$ and a finite number of vectors $x_1, \dots, x_k \in V$. Then, every $v \in V$ of the form

\[v = \lambda _1 x_1 + \dots + \lambda _k x_k = \sum_{i = 1}^{k} \lambda_i x_i \in V\]with $\lambda _1, \dots, \lambda _k \in \mathbb{R}$ is a linear combination of the vectors $x_1, \dots, x_k$.

Linear (in)/dependence: Let’s consider a vector space $V$ with $k \in \mathbb{N}$ and $x_1, \dots, x_k \in V$. If there is a non-trivial linear combination, such that $\pmb{0} = \sum_{i = 1}^{k} \lambda_i x_i$ with at least one $\lambda_i \neq 0$, the vectors $x_1, \dots, x_k$ are linearly dependent. If only the trivial solution exists, ie $\lambda_1 = \dots = \lambda_k = 0$ the vectors $x_1, \dots, x_k$ are linearly independent.

- Intuitively, we can think of a set of linearly independent vectors as a combination of vectors with no redudancy, where removing any vector will reduce our span. No two vectors sit on the same line or can be scaled by some $\lambda_i$ to be equal to each other.

Properties of determining linear (in)/dependence:

- $k$ vectors can only be linearly dependent or linearly independent.

- if any one of the vectors $x_1, \dots, x_k$ is $\pmb{0}$ or any two vectors are equal to each other, than they are linearly dependent.

- The vectors $\{x_1, \dots, x_k : x_i \neq \pmb{0}, i = 1, \dots, k \}, k \geq 2$ are linearly dependent iff at least one of the vectors is a linear combination of the others.

Basis and Rank

Generating Set and Span: Consider a vector space $V = (\mathcal{V}, +, \cdot)$ and set of vectors $\mathcal{A} = \{x_1,\dots, x_k \} \in \mathcal{V}$. If every vector $\pmb{v} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be expressed as a linear combination of $x_1, \dots, x_k, \mathcal{A}$ is called a generating set of $V$. The set of all linear combinations of vectors in $\mathcal{A}$ is called the span of $\mathcal{A}$. If $\mathcal{A}$ spans the vector space $V$, we write $V = span[A]$ or $V = span[x_1,\dots, x_k]$.

- Generating sets are sets of vectors that span vector (sub)spaces (every vector can be represented as a linear combination of the vectors in the generating set).

Basis: Consider a vector space $V = (\mathcal{V}, +, \cdot)$ and $\mathcal{A} \subseteq \mathcal{V}$. A generating set $\mathcal{A}$ of $V$ is called minimal if there exists no smaller set $\tilde{\mathcal{A}} \subsetneq \mathcal{A} \subseteq \mathcal{V}$ that spans $V$. Every linearly independent generating set of $V$ is minimal and is called a basis of $V$.

Let $V = (\mathcal{V}, +, \cdot) $ be a vector space and $\mathcal{B} \subseteq \mathcal{V}, \mathcal{B} \neq \emptyset$. THen, the following statements are equivalent:

- $\mathcal{B}$ is a basis of $V$.

- $\mathcal{B}$ is a minimal generating set.

- $\mathcal{B}$ is a maximal linearly independent set of vectors in $V$ (adding any other vector will make it linearly dependent).

- Every vector $\pmb{x} \in V$ is a linear combination of vectors from $\mathcal{B}$, and every linear combination is unique, ie, with

Rank: The number of linearly independent columns of a matrix $\pmb{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ equals the number of linearly independent rows and is called the rank of $\pmb{A}$ and is denoted by rk($\pmb{A}$). The rank of a matrix has these properties:

- rk($\pmb{A}$) = rk($\pmb{A}^T$)

- The columns of $\pmb{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ span a subspace ${U} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^m$ with dim(${U}$) = rk($\pmb{A}$). This subpace is called an image or range.

- The rows of $\pmb{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ span a subspace ${W} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n$ with dim(${W}$) = rk($\pmb{A}$).

- For all $\pmb{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$ it holds that $\pmb{A}$ is invertible iff $rk(\pmb{A}) = n$.

- For all $\pmb{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ and all $\pmb{b} \in \mathbb{R}^m$ it holds that the linear equation system $\pmb{Ax = b}$ can be solved iff $rk(\pmb{A}) = rk(\pmb{A \mid b})$.

- For $\pmb{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ the subspace of solutions for $\pmb{Ax = 0}$ possesses dimension $n - rk(\pmb{A})$. This subspace is called the kernel or the null space.

- A matrix $\pmb{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ has full rank if its rank equals the largest possible rank for a matrix of the same dimensions $(rk(\pmb{A}) = min(m, n))$. A matrix is rank deficient if it doesn’t have full rank.

Linear Mappings

Linear Mapping: For vector spaces $V, W,$ a mapping $\Phi : V \to W$ is called a linear mapping (also called vector space homomorphism/linear transformation) if

\[\forall \pmb{x, y} \in V \forall \lambda, \psi \in \mathbb{R} : \Phi (\lambda \pmb{x} + \lambda \pmb{y}) = \lambda \Phi (\pmb{x}) + \psi \Phi (\pmb{y})\]Consider a mapping $\Phi : \mathcal{V} \to \mathcal{W}$, where $\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{W}$ can be arbitary sets. Then $\Phi$ is called

- injective if $\forall \pmb{x, y} \in \mathcal{V} : \Phi(\pmb{x}) = \Phi(\pmb{y}) \Longrightarrow \pmb{x} = \pmb{y}$: every element in $\mathcal{W}$ can be “reached” from $\mathcal{V}$ using $\Phi$.

- surjective if $\Phi(\mathcal{V}) = \mathcal{W}$. A bijective $\Phi$ can be “undone”: there exists a mapping $\Psi : \mathcal{W} \to \mathcal{V}$ so that $\Psi \circ \Phi = x$.

- bijective if it is injective and surjective

We define the following special cases of linear mappings between vector spaces $V$ and $W$:

- Isomorphism: $\Phi : V \to W$ linear and bijective

- Endomorphism: $\Phi : V \to V$ linear

- Automorphism: $\Phi : V \to V$ linear and bijective

- We define $id_v : V \to V, x \mapsto x$ as the identity mapping or identity automorphism in $V$.

Theorem: Finite-dimensional vector spaces $V$ and $W$ are isomorphic if and only if $dim(V) = dim(W)$.

- This theorem states that there exists a linear, bijective mapping between two vectors in the same dimension. Intuitively this means that vector spaces of the same dimension are the same, as they can be transformed into each other without incurring any loss.

Any $n$-dimension vector space is isomorphic to $\mathbb{R}^n$. We consider a basis $\{b_1, \dots, b_n\}$ of an $n$-dimensional vector space $V$. The order of the basis vectors is important so we write

\[B = (b_1, \dots, b_n)\]and call this $n$-tuple an order basis of $V$.

Coordinates: Consider a vector space $V$ and an ordered basis $B = (\pmb{b}_1, \dots, \pmb{b}_n)$ of $V$. For any $x \in V$, we obtain a unique representation (linear combination)

\[x = \alpha_1 \pmb{b}_1 + \dots + \alpha_n \pmb{b}_n\]of $x$ with respect to $B$. Then $\alpha_1, \dots, \alpha_n$ are the coordinates of $x$ with respect to $B$ and the vector

\[\alpha = \begin{bmatrix} \alpha_1 \\\ \vdots \\\ \alpha_n \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^n\]is the coordinate vector/coordinate representation of $x$ with respect to the order basis $B$.

Consider vector spaces $V, W$ with corresponding ordered bases $B = (\pmb{b}_1, \dots, \pmb{b}_n)$ and $C = (\pmb{b}_1, \dots, \pmb{b}_n)$. We consider a linear mapping $\Phi : V \to W $. For $j \in \{1, \dots, n \}$,

\[\Phi (\pmb{b}_j) = \alpha_{1j} \pmb{c}_1 + \dots + \alpha_{mj}\pmb{c}_m = \sum_{i = 1}^{m} \alpha_{ij}\pmb{c}_i\]is the unique representation of $\Phi \pmb{b_j}$ with respect to $C$. Then we call the $m \times n$-matrix $\pmb{A}_\phi$, whose elements are given by

\[A_\Phi(i, j) = \alpha_{ij}\]the transformation matrix of $\Phi$.

The coordinates of $\Phi \pmb{b_j}$ with respect to the order basis $C$ of $W$ are the j-th column of $\pmb{A}_{\Phi}$. Consider (finite-dimensional) vector spaces $V, W$ with ordered bases $B, C$ and a linear mapping $\Phi : V \to W$ with transformation matrix \(\pmb{A}_{\Phi}\). If $\hat{x}$ is thee coordinate vector $x \in V$ with respect to $B$ and $\hat{y}$ the coordinate vector $y = \Phi (x) \in W$ with respect to $C$, then

\[\hat{y} = \pmb{A}_\Phi\hat{x}\]THis means that the transformation matrix can be used to map coordinates with respect to an ordered basis in $V$ to coordinates with respect to an ordered basis in $W$.

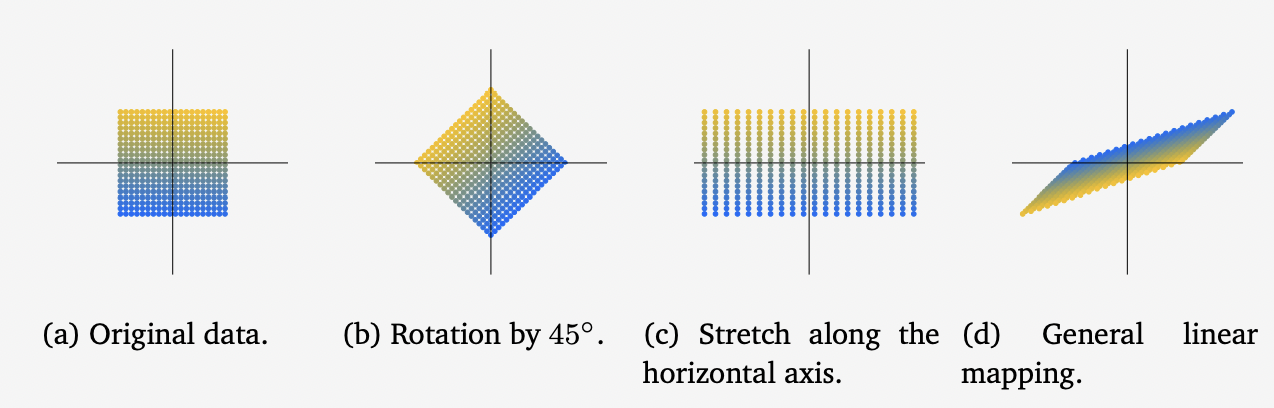

The following are three linear transformations on a set of vectors in $\mathbb{R}^2$.

- b = \(\begin{bmatrix} cos(\frac{\pi}{4}) & -sin(\frac{\pi}{4}) \\\ sin(\frac{\pi}{4}) & cos(\frac{\pi}{4}) \end{bmatrix}\) which is equivalent to a $45^\circ$ rotation.

-

c = \(\begin{bmatrix} 2 & 0 \\\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\) which is a stretching of the horizontal coordinates by 2.

- d = \(\frac{1}{2} \begin{bmatrix} 3 & -1 \\\ 1 & -1 \end{bmatrix}\) which is a combination of reflection, rotation and stretching.

Basis Change: For a linear mapping $\Phi : V \to W$, ordered bases

\(B = (b_1, \dots, b_n), \; \; \tilde{B} = (\tilde{b}_1, \dots, \tilde{b_n})\)

of V and

\(C = (c_1, \dots, c_n), \; \; \tilde{C} = (\tilde{c}_1, \dots, \tilde{c_n})\)

of W, and a transformation matrix $A_{\Phi}$ of $\Phi$ w.r.t $B$ and $C$, the corresponding transformation matrix $A_\Phi$ w.r.t the bases $\tilde{B}$ and $\tilde{C}$ is given as

where $S \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$ is the transformation matrix of $id_v$ that maps coordinates w.r.t $\tilde{B}$ onto coordinates w.r.t $B$, and $T \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times m}$ is the transformation matrix of $id_w$ that maps coordinates w.r.t $\tilde{C}$ onto coordinates w.r.t $C$.

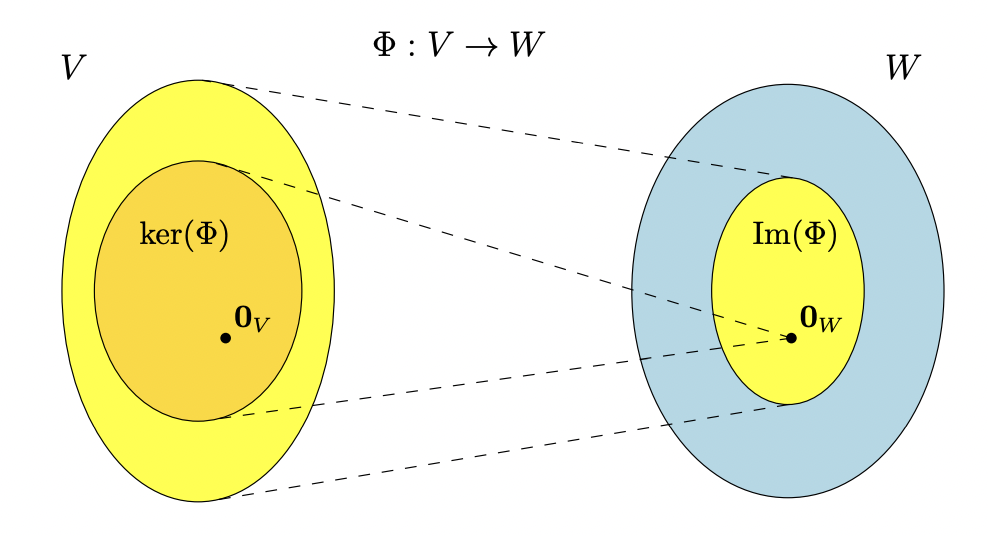

For $\Phi: V \to W$ we define the kernel/null space

\[ker(\Phi):= \Phi^{-1}\pmb{0}_w = \{\pmb{v} \in V : \Phi{\pmb{v}} = \pmb{0}_w \}\]and the image/range

\[Im(\Phi) := \Phi(V) = \{\pmb{w} \in W |\exists \pmb{v} \in V : \Phi(\pmb{v}) = \pmb{w} \}\]We call $V$ the domain and $W$ the codomain of $\Phi$.

Intuitively, we can think of the kernel as the set of vectors $v \in V$ that $\Phi$ maps onto the neutral element $0_w \in W$. The image is the set of vectors $w \in W$ that can be “reached” by $\Phi$ from any vector in $V$.

- $\Phi$ is injective (one-to-one) iff $ker(\Phi) = \{\pmb{0}\}$

Calculus

Derivative: The derivative of a function $f$ tells us the average slope of a function.

\[\frac{df}{dx} := \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x + h) - f(x)}{h}\]Some basic but important differentiation rules:

- Product rule: $(f(x)g(x))’ = f’(x)g(x) + f(x)g’(x)$

- Quotient rule $(\frac{f(x)}{g(x)})’ = \frac{f’(x)g(x) - f(x)g’(x)}{(g(x))^2} $

- Sum rule: $(f(x) + g(x))’ = f’(x) + g’(x)$

-

Chain rule: $(g(f(x)))’ = (g \circ f)’(x) = g’(f(x))f’(x)$

- $g \circ f$ denotes function composition $x \mapsto f(x) \mapsto g(f(x))$

Partial derivates: For a function $f: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}, x \mapsto f(\pmb{x}), \pmb{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$ of $n$ variables $x_1,\dots, x_n$ we define the partial derivative as

\[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1} = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x_1 + h, x_2, \dots x_n) - f(\pmb{x})}{h}\] \[\vdots\] \[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n} = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x_1,\dots,x_{n - 1}, x_n+ h) - f(\pmb{x})}{h}\]and collect them in the row vector

\[\nabla_x f = grad f = \frac{df}{dx} = \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1} & \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_2} & \dots & \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n} \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times n}\]where $n$ is the number of variables and 1 is the dimension of the image/range/codomain of $f$. We call this row vector the gradient of $f$.